Contents

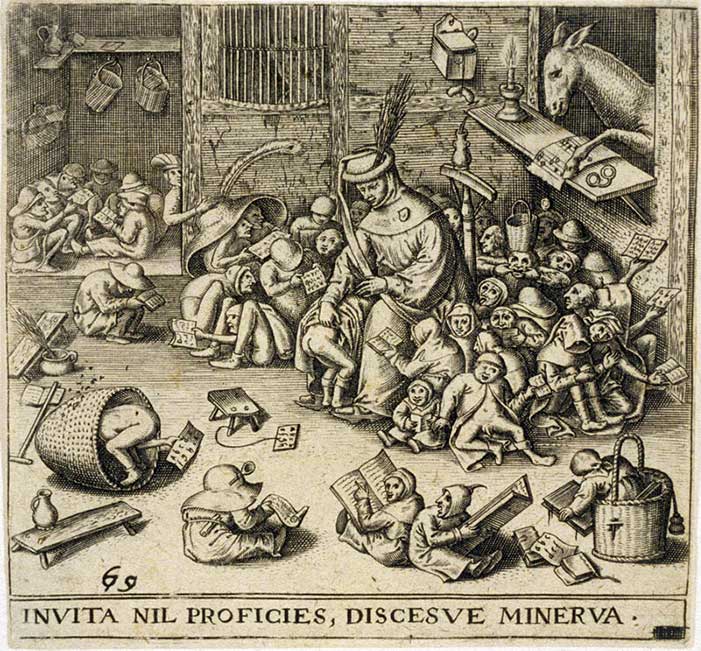

Have you ever done something Invita Minerva? Most people have.

Have you ever said you have a lovely singing voice, but once on stage, you sound like an angry pig?

Have you ever tried to come up with a lesson plan to end all lesson plans for your class, only to pull your hair out in despair and end up with the same sort of lesson plan you always do?

Or have you perhaps spent hours in front of an angry-looking blank paper, even though, last time you checked, it said “author” on your card? Then maybe you have been trying to do things Invita Minerva.

More Latin Proverbs: Auribus Teneo Lupum: Why Emperor Tiberius and President Thomas Jefferson Both Held a Wolf by the Ears

Totally Talentless

Sometimes we do things that we have no talent for. Sometimes we lose a bet and are forced to do something, sometimes we are just too ignorant to realize we are unqualified for something and sometimes we find ourselves in situations we know nothing about and have to wing it.

When you try to do something against your bent, something you are totally unqualified for or have no talent what-so-ever for – be it paint, sing, cook, build, knit, write, speak – the Romans would express this with a little help from the goddess Minerva:

“Invita Minerva! ”

i.e. “Unwilling Minerva!”

Without Wisdom

Minerva was the Roman goddess of wisdom, art, and talent. So when you try to do something without her help, i.e., without talent or wisdom, or without a willing Minerva, that would mean you go against the goddess herself, which means going against the heavens and so in defiance of nature itself.

Cicero was fond of this expression and used it several times. In De officiis 1.110.10 he used the proverb to bring home an argument about peoples’ gifts and that we must hold on to them and not go against our natural geniuses. He wrote:

“Sic enim est faciendum, ut contra universam naturam nihil contendamus, ea tamen conservata propriam nostram sequamur, ut, etiamsi sint alia graviora atque meliora, tamen nos studia nostra nostrae naturae regula metiamur; neque enim attinet naturae repugnare nec quicquam sequi, quod assequi non queas. Ex quo magis emergit, quale sit decorum illud, ideo quia nihil decet invita Minerva, ut aiunt, id est adversante et repugnante natura.”

i.e., “For we must so act as not to oppose the universal laws of human nature, but, while safeguarding those, to follow the bent of our own particular nature; and even if other careers should be better and nobler, we may still regulate our own pursuits by the standard of our own nature. For it is of no avail to fight against one’s nature or to aim at what is impossible of attainment. From this fact, the nature of that propriety defined above comes into still clearer light, inasmuch as nothing is proper that “goes against the grain,” as the saying is—that is if it is in direct opposition to one’s natural genius.” (transl. Miller, 1913)

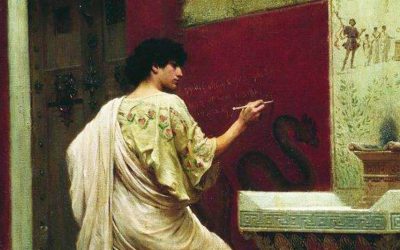

Prudent Poet

The expression has also been used figuratively, where an unwilling Minerva might not be as harsh as going against the gods and nature, but rather having a lack of inspiration. Or at least not having the muses at your side, be it temporarily or not.

For instance, you need Minerva on your side to be a good artist. The great poet Horace lets us know that it is good sense NOT to go against Minerva. He wrote:

“Tu nihil invita dices faciesve Minerva;

id tibi iudicium est, ea mens.”

— Horatius, Ars Poetica 385

i.e. “But you will say nothing and do nothing against Minerva’s will; such is your judgement, such your good sense.” (transl. Rushton Fairclough, 1926)

No Help For Hymns

For a long time the expression has had a special place in the hearts of poets as either an excuse for bad poetry or as a way to express a lack of inspiration. In Sweden one could, only a hundred years ago, still use the expression as it was. In a book about the Swedish 18th century hymn writer Samuel Ödmann you can read that Ödmann:

”invita Minerva.”

i.e. (roughly translated) “…often jokes about the bad verses he’s cobbled together and gladly agrees that they have come into being invita Minerva.”

Ödmann himself opined that you had to be born a poet, and was not convinced he had been so lucky.

Minerva The Muse

If the goddess is unwilling, she will not come to you when you need her for inspiration or help or education. Even if you call upon her, she might not come and there you sit in front of you blank paper, or canvas.

Without the help of Minerva your work will be so much heavier, it will be a struggle, and the outcome might not be so grand. It does not matter that you are talented or skillful, without her help, there you are feeling like an ass trying to cut a wet log in half against its grains.

The 19th century american poet/author Thomas Bailey Aldrich even dedicated a poem to Minerva and named it ”Invita Minerva”, where the will of the Muse, the inspiration, rarely comes when you seek it:

“Not of desire alone is music born,

Not till the Muse wills is our passion crowned;

Unsought she comes; if sought, but seldom found,

Repaying thus our longing with her scorn.

Hence is it poets often are forlorn,

In super-subtle chains of silence bound,

And mid the crowds that compass them around

Still dwell in isolation night and morn,

With knitted brow and cheek all passion-pale

Showing the baffled purpose of the mind.

Hence is it I, that find no prayers avail

To move my Lyric mistress to be kind,

Have stolen away into this leafy dale

Drawn by the flutings of the silvery wind.”

Cicero To Cornificius

The saying can also be used negated, meaning Minerva was with you and everything you worked on turned out great!

For instance, Cicero writes in a letter to Cornificius:

“Quinquatribus frequenti senatu causam tuam egi, non invita Minerva.”

— Cicero, Fam. 12.25

i.e. “On Minerva’s Day [Quinquatria] I pleaded your cause at a well attended session, not without the Goddess’ [Minerva’s] good will.” (transl. Shackelton Bailey, 2001)

Resources

Cicero. On Duties. Translated by Walter Miller. Loeb Classical Library 30. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1913.

Horace. Satires. Epistles. The Art of Poetry. Translated by H. Rushton Fairclough. Loeb Classical Library 194. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1926.

Cicero. Letters to Friends, Volume III: Letters 281–435. Edited and translated by D. R. Shackleton Bailey. Loeb Classical Library 230. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001.